Membaca adalah salah catu bagian dari proses belajar yang penting. Di era Internet ini, ada beberapa sumber belajar lain selain bahan bacaan. Misalnya berbagai video instruksional yang menunjukkan bagaimana caa melakukan sesuatu. Ada pula audiobook yang membuat orang bisa mengetahui isi suatu bacaan melalui media suara, cukup dengan mendengarkan. Ada pula podcast dengan isi penyampaian dari seorang pembica atau perbincangan dari beberapa orang. Namun demikian membaca masih menjadi kegiatan yang sangat penting dari proses belajar.

Ada beberapa cara membaca dan belajar yang baik yang berguna untuk pelajar dan semua orang yang sedang belajar, termasuk mahasiswa. Di antara yang dapat dipraktikkan adalah metode PSQ5R. Metode ini memiliki beberapa variasi, (di antaranya yang bisa jadi adalah pendahulunya) semisal SQ3R seperti pada Gambar 1.

Gambar 1.

Gambar 1. Gambar 2. Contoh PSQ5R.

Gambar 2. Contoh PSQ5R.

Gambar 2 adalah mind map yang menyederhanakan keseluruhan proses dalam PSQ5R dan dipergunakan untuk mempelajari bahan bacaan mengenai Power Electronics. Detail mengenai PSQ5R dapat dengan mudah dicari di Internet dengan mencantumkan kata-kata kunci di mesin pencari seperti Google maupun Bing.

[intense_panel shadow=”4″ title=”Penyalinan” title_color=”#ebebeb” title_font_color=”#ff0000″ border=”1px solid #cfc0c0″]

Keterangan mengenai PSQ5R berikut ini saya salin dari halaman: http://www.yugzone.ru/speed_reading/speedreading/r025.html. Disalin ulang di sini untuk menjamin ketersediaan saat belajar. Silakan menuju situs asal untuk membaca lengkap dan gunakan ScrapBook untuk lebih menjamin ketersediaan bacaan.

[/intense_panel]

[su_panel border=”2px solid #26fb8d” shadow=”1px 2px 2px #eeeeee” radius=”5″]

What is the purpose of reading

Why are you reading this article or chapter, and what do you want to get out of it? When you have accomplished your purpose, stop reading. For instance, your purpose in seeking a number in the telephone book is specific and clear, and once you find the number, you stop “reading.” Such “reading” is very rapid indeed, perhaps 100,000 word a minute! Perhaps it should be called by its proper name, “scanning”, but when it suits your purpose, it is fast and efficient. This principle, of first establishing your purpose, whether to get the Focus or Theme, or main ideas, or main facts or figures, or evidence, arguments and examples, or relations, or methods, can prompt you to use a reading method that gets what you want in the minimum time.

Survey or skim the text

Glance over the main features of the piece, the lead and summary paragraphs, look at the title, the headings, to find out what ideas, to get an overview of the piece, problems and questions are being discussed. In doing this you should find the Focus of the piece that is, the central theme or subject, what it is all about; and perhaps the Perspective, that is, the approach or manner in which the author treats the theme. This survey should be carried out in no more than a minute or two.

Ask the question

Compose questions that you aim to answer:

What do I already know about this topic? – In other words, activate prior knowledge. Turn the first heading into a question, to which you will be seeking the answer when you read. For example: “What were ‘the effects of the Hundred Years’ War’?” – and you might add “on democracy, or on the economy”? Or “What is ‘the impact of unions on wages’?”

Read the text selectively

Read to find the answers to your question. By reading the first sentence of each paragraph you may well get the answers. Sometimes the text will “list” the answers by saying “The first point is … Second point is…” and so on. And in some cases you may have to read each paragraph carefully just to understand the next one, and to find the Focus or main idea buried in it. In general, look for the ideas, information, evidence, etc., that will meet your purpose.

Recite

Without looking at the book, recite the answers to the question, using your own words as much as possible. If you cannot do it reasonably well, look over that section again.

Reduce and record

Make a brief outline of the question and your answers. The answers should be in key words or phrases, not long sentences. For example, “Effects of 100 Yrs’ War? – consolidate Fr. King’s power, Engl. off continent”. Or, “Unions on Wages? – Uncertain, maybe 10-15%”.

Reflect the information

Recent work in cognitive psychology indicates that comprehension and retention are increased when you “elaborate” new information. This is to reflect on it, to turn it this way and that, to compare and make categories, to relate one part with another, to connect it with your other knowledge and personal experience, and in general to organize and reorganize it. This may be done in your mind’s eye, and sometimes on paper. Sometimes you will at this point elaborate the outline of step 6, and perhaps reorganize it into a standard outline, a hierarchy, a table, a flow diagram, a map, or even a “doodle.” Then you go through the same process, steps 3 to 7, with the next section, and so on.

Review the text

Survey your “reduced” notes of the paper or chapter to see them as a whole. This may suggest some kind of overall organization that pulls it all together. Then recite, using the questions or other cues as starters or stimuli for recall. This latter kind of recitation can be carried out in a few minutes, and should be done every week or two with important material.

Selain metode atau cara membaca, yang juga penting dalam belajar adalah mencoba memahami bagaimana data dan informasi dapat dipertahankan dalam ingatan. Atau yang lebih baik adalah memahami mengapa kita sering perlu belajar hal yang sama berulang-ulang.

[intense_panel shadow=”4″ title=”Penyalinan” title_color=”#ebebeb” title_font_color=”#ff0000″ border=”1px solid #cfc0c0″]

Keterangan berikut merupakan salinan. Disalin ulang di sini untuk menjamin ketersediaan saat belajar. Silakan menuju masing-masing situs asal untuk membaca lengkap dan gunakan ScrapBook untuk lebih menjamin ketersediaan bacaan.

[/intense_panel]

[su_panel border=”2px solid #FFBF00″ shadow=”1px 2px 2px #FFBF00″ radius=”5″]

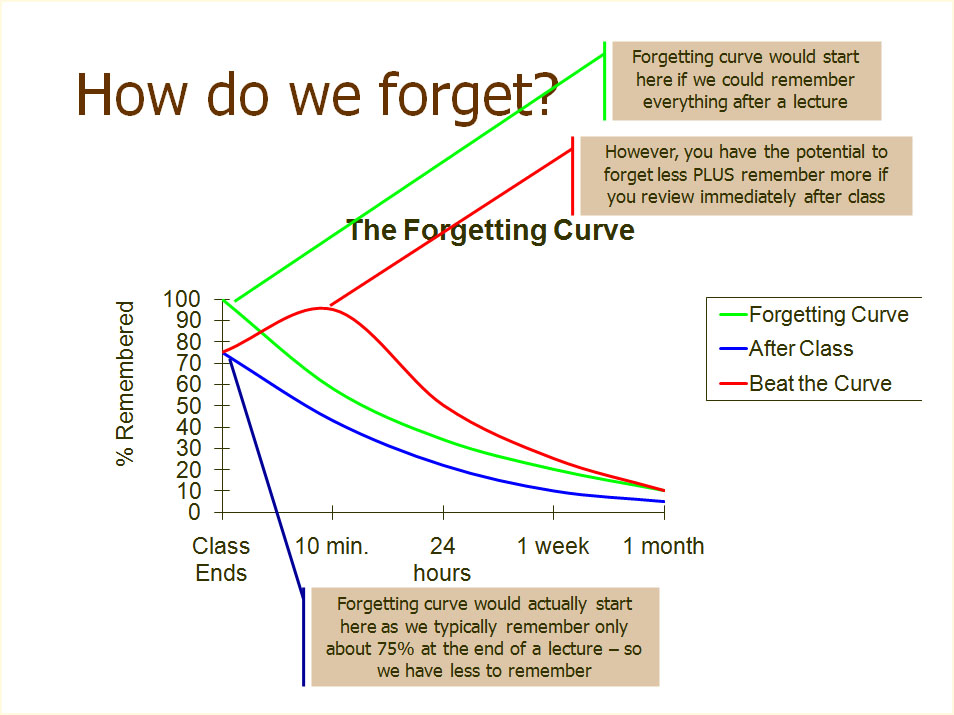

Gambar 3. The Curve of Forgetting.

You can change the shape of the curve! Reprocessing the same chunk of information sends a big signal to your brain to hold onto that data. When the same thing is repeated, your brain says, “Oh – there it is again, I better keep that.” When you are exposed to the same information repeatedly, it takes less and less time to “activate” the information in your long term memory and it becomes easier for you to retrieve the information when you need it.

Here’s the formula and the case for making time to review material: within 24 hours of getting the information – spend 10 minutes reviewing and you will raise the curve almost to 100% again. A week later (day 7), it only takes 5 minutes to “reactivate” the same material, and again raise the curve. By day 30, your brain will only need 2-4 minutes to give you the feedback, “yes, I know that…”

–sumber: https://uwaterloo.ca/counselling-services/curve-forgetting

[/su_panel]

[su_panel border=”2px solid #86729C” shadow=”1px 2px 2px #86729C” radius=”5″]

Gambar 4.

Gambar 4.

–sumber: http://www.byui.edu/learning-and-teaching/news/lest-they-forget

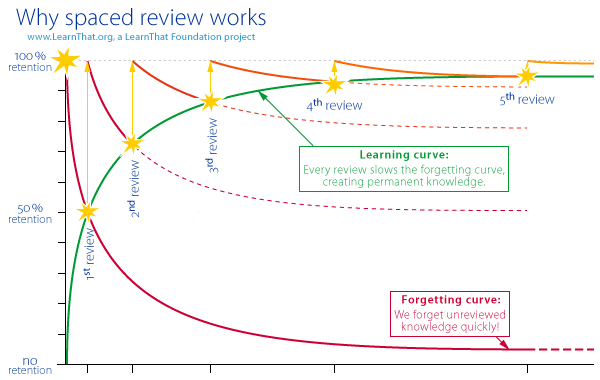

Gambar 5.

Gambar 5.

–sumber: learnthat.org

[/su_panel]

[su_panel border=”2px solid #80B3FF” shadow=”1px 2px 2px #80B3FF” radius=”5″]

What is the Spacing Effect?

When we talk about the spacing effect, we are talking about spacing repetitions of learning points over time. The spacing effect occurs when we present learners with a concept to learn, wait some amount of time, and then present the same concept again.

Spacing can involve a few repetitions or many repetitions. Spaced repetitions need not be verbatim repetitions. Repetitions of learning points can include the following:

- Verbatim repetitions.

- Paraphrased repetitions (changing the wording slightly).

- Stories, examples, demonstrations, illustrations, metaphors, and other ways of providing context and example.

- Testing, practice, exercises, simulations, case studies, role plays, and other forms of retrieval practice.

- Discussions, debate, argumentation, dialogue, collaboration, and other forms of collective learning.

The following findings are highlighted in the report:

- Repetitions—if well designed—are very effective in supporting learning.

- Spaced repetitions are generally more effective than non-spaced repetitions.

- Both presentations of learning material and retrieval practice opportunities produce benefits when utilized as spaced repetitions.

- Spacing is particularly beneficial if long-term retention is the goal—as is true of most training situations. Spacing helps minimize forgetting.

- Wider spacings are generally more effective than narrower spacings, although there may be a point where spacings that are too wide are counterproductive. A good heuristic is to aim for having the length of the spacing interval be equal to the retention interval.

- Spacing repetitions over time can hurt retrieval during learning events while it generates better remembering in the future (after the learning events).

- Gradually expanding the length of spacings can create benefits, but these benefits generally do not outperform consistent spacing intervals.

- One way to utilize spacing is to change the definition of a learning event to include the connotation that learning takes place over time—real learning doesn’t usually occur in one-time events.

So what is the spacing effect? It is the finding that spaced repetitions produce more learning—better long-term retention—than repetitions that are not spaced. It is also the finding that longer spacings tend to produce more long-term retention than shorter spacings (up to a point where even longer spacings are sometimes counterproductive).

Note that distributing unrelated, non-repetitious learning events over time does not officially constitute the spacing effect. When we give learners a rest between learning sessions, we may limit their learning fatigue, but we’re not necessarily providing them with all the advantages that spacing can provide. Again, the spacing effect occurs when

repetitions of learning points are distributed over time.

What Causes the Spacing Effect?

Despite the fact that the spacing effect is one of the most studied phenomena in the field of learning research its causes are still being debated and discussed. The following reasonable explanations have been put forth:

1. Wider spacings require extra cognitive effort and such effort creates stronger memory traces and better remembering.

2. Wider spacings create memory traces that are more varied than narrow spacings, creating multiple retrieval routes that aid remembering.

3. Wider spacings produce more forgetting during learning, prompting learners to use different and more effective encoding strategies that aid remembering in the future.

— sumber: Spacing_Learning_Over_Time__March2009v1_.pdf

[/su_panel]